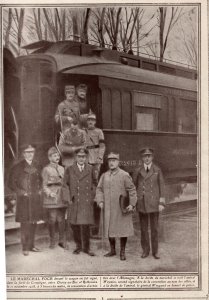

The Great War formally ended at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 – surely the most poetically timed Armistice in history. The agreement had actually been signed at 5.10am, in General Foch’s railway carriage in the Forest of Compiègne, but extra time was needed for the news to reach the various fighting fronts.

Stroud had been on tenterhooks. ‘No week…in all history can compare with these wonderful seven days of historic happenings’, gushed the News, in its first peacetime edition, published on Friday, 15th November. The official bulletin had been posted outside the newspaper’s offices:

…that was shortly before eleven, and with the stroke of the hour the bell at Messrs. Holloways factory clanged forth, the Syrens [sic] at the local mills were sounded and within an incredibly short time the streets were filled with excited citizens and bright faced, never may care schoolchildren.

The announcement had been eagerly expected, and indeed premature rejoicing, based on rumour, had taken place a whole hour in advance among the local Australians…

However the newspaper scrupulously and sympathetically noted that:

To say that all were delighted would be to perpetuate an untruth. Unfortunately too many were borne down in sorrow and it was the lot of our reporter to meet many suffering mothers and widows hurrying from workshop and mills to their cottage homes to silently mourn the loss of loved ones who had gone…one mother had lost no fewer than five sons.

Drapers sold red, white and blue ribbon (for bows and rosettes) ‘like wildfire’, flags appeared everywhere, and the VTC fired blank rounds from the Sub Rooms balcony. The Town Band played patriotic music in King Street Parade.

In Chalford:

All were on the “tip-toe” of expectation for the glad tidings on Monday morning, and, when , about eleven o’clock, telephonic enquiry at the ‘Stroud Journal’ Office elicited the reply that official news had been received of the signing of the Armistice, a prolonged blast on the hooter at Bliss Mills was the signal for general rejoicing…Flags were displayed, the bells at the Parish Church were rung, and the firing of cannon from Mr James Smart’s wharf and elsewhere materially helped to spread the glad tidings in the villages and hamlets on the top of the hills and hillsides. Business was entirely suspended “on all fronts”, and sane jollity reigned supreme to a late hour at night. On receipt of the news, the children of the Chalford Hill Council School, together with their esteemed Headmaster (Mr FA Webster) and teachers, paraded the village, singing school and other songs en route, and also stopping at the various greens to give vent to their feelings in song and cheering.

A large number of people gathered at the Parish Church to give praise and thanksgiving to God for victory and other blessings, the service…being conducted by the Rev AE Addenbrooke, vicar, and the singing heartily joined in by the congregation. As usual, the church remained open during the day for private worship, and many repaired thither to humbly render thanks to Almighty God.

A similar service was held at France Lynch Church in the evening…

Bisley had a problem in that its usual method of reacting to positive news was ringing the church bells – however most of the ringers were away at the Front, so they had to improvise:

…the place contains handbells of varying grades of sonorousness, and these were collected by a number of young people, including a dignified member of the nursing profession, who ventured forth, a bell in either hand, and rang in the good news with muscle-straining vigour.

The papers had to treat with less happy news, however, as reports of deaths of local servicemen continued to be notified.

Harry (Henry George William) Philpots (or Philpotts) had been killed on October 12th, fighting with the 7th Canadians in the attack on the Canal-de-la-Sensée. He had been born and brought up in France Lynch, but by 1911 he had moved to Cheshire, where he was working as a valet. Described as ‘a dutiful son and a gallant young fellow’, the Journal explained that:

Previous to crossing the Atlantic, he had been in ill-health for a long time, and a gentleman who took an interest in him was the means of his emigrating to Canada, where he was getting on very nicely. He responded to his country’s call in February ,1915, and soon became an efficient soldier and popular with his colleagues.

His officer wrote to his parents: ‘He had charge of one of the Lewis gun sections in my platoon. He was a very capable NCO, and is sadly missed by us all’. Another tribute was quoted in the paper:

We have lost a good friend and comrade, and you a dear son, in the death of Harry, and our sympathies are with you…Harry was a good soldier, a great personality, and a friend of all who knew him.

The family had already lost their youngest child, Christopher, killed in January 1918. The remaining members, George, Elizabeth and their two daughters Lily and Alma, would have been among those for whom the rejoicing at the Armistice felt very hollow indeed.

Albert Robbins’ wife, Alice, heard the day after the Armistice that he had been killed. A quarryman who lived in Bournes Green, near Oakridge, ‘he joined up early in the war and therefore had seen considerable service at the Front’. He had been ‘on the Reserve’, having previously served in the Glosters. Though involved in ‘stiff fighting’ early on in the war, he had been drafted to the cook house for two years (possibly because of his age – he was 37 at the outbreak of war), until he requested a return to more active service. He was killed ‘during the taking of Catillon prior to crossing the Sambre Canal on November 4th’ (the same place and day that saw the death of the poet Wilfred Owen). His officer, Captain WH Hodges, who hailed from Thrupp, wrote to the vicar of Oakridge, asking him to break the news to Alice, and saying:

He was one of our best men, always very cool and brave under fire. His death was instantaneous. He was killed by machine gun fire, and has been buried in an orchard near the village.

In 1911, the Robbins were shown as having four living children, the oldest of whom, Hilda, aged 13, was described as a ‘cripple’.

Ernest Hill, who lived in the Vale, ‘arrived home on Tuesday [12th November], but shortly afterwards was taken seriously ill. Unfortunately he had been gassed on no fewer than four occasions’. Happily, the next week’s paper carried the news that Sergeant Hill had recovered.

The parents of Charles Franklin had received ‘an interesting letter’ from their son, who was a POW. Writing before the end of the war, he expressed ‘strong indignation at the treatment meted out to him by the Germans’. He had been incarcerated in Hameln Camp, Germany, but recently moved to an internment camp in Holland:

Remarking that it was a very long time since he saw his relatives, and that he hardly knew ‘who is who’, he added that he was eagerly looking forward to coming home again…’I am very glad to have my freedom, but one wants plenty of money’…(Stroud Journal, 15-11-18)

Now the war was officially over, the focus would gradually shift to domestic matters. Of these, the most pressing was the imminent general election, called immediately after the announcement of the Armistice, in which all men over the age of 21 and some women would be allowed to vote for the first time.