I can’t imagine how that festive season would have felt, 1918-19. After all, Christmas 1918 fell only just over a month after the Armistice. Most servicemen were still far from home, shops were still experiencing shortages, and many families had lost one or more deeply cherished members. Unsurprisingly, Christmas that year was described as ‘quiet’ and ‘domestic’, with ‘sadness in many homes’.

Deeply aware of the physical legacy of war, people were keen to continue fund-raising. In Bisley:

A Carol League was formed the second week in November and six or seven practices of special music were held. A band of carollers, led by Mr Bloodworth [the school master], paraded Bisley and Eastcombe on Christmas Eve and the evening of Christmas Day and over £10 was collected. The four-part music, very tunefully rendered in the open air to the accompaniment of a portable harmonium, gave much pleasure.

More money was contributed at a variety concert held in the school on New Year’s Day, giving a total of £25 for St Dunstan’s Hostel for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors. Obviously ‘carolling for St Dunstan’s’ was a thing, because a similar initiative took place in Stroud, where £70 12/4d was raised over ‘fourteen consecutive evenings’. A letter to the ‘Journal’, published on 17th January, compares 1918’s total favourably with that of 1917 (£54 3/5d) and 1916 (£25).

There was yet another ‘flu burial at France Lynch. Reginald E Barrett, a boy of only 17, had died on Christmas Eve. He had worked at Chalford Aerodrome, and also done war work in Birmingham, and the ‘Journal’ commented:

…his death adds to the already long list of boys who from the hamlet of France Lynch have laid down their lives either on active service, or in helping their comrades at the front.

Further mention was made of Douglas Webster’s Military Cross, the ‘Journal’ quoting his local Canadian newspaper (in Regina, Saskatchewan), ‘The Morning Leader’, which gave a summary of his enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in October 1914, his promotion to Sergeant in the Signallers, and later to Lieutenant. The paper went on to describe how he had won the medal for his actions near Amiens ‘clearing out a machine gun nest’. Mainly, the paper was interested in his pre-war civilian life, as a keen footballer:

Lieut Webster will be best remembered by the soccer fooball fraternity of the city, among whom he was known as the sterling right half of the old United Club. In France he maintained his football reputation as a good defence man in games between the Canadians and Imperials…

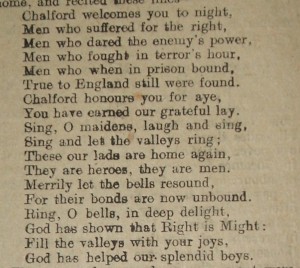

His father Frank, the probable source of the Canadian cutting, had been busily engaged writing a poem for the welcome home event held for returned POWs at the Primrose Hall on 17th January:

He compered the evening, congratulating the men ‘on being alive, on having survived a diet of black bread and dirty water, yclept [called] soup,the brutality of the big booted Hun, and that they had not been entirely eaten up by unmentionable creepy-crawlies’. There was sufficient money left over from fund-raising to provide every man with a sovereign and a packet of cigarettes.

Percy Abel, Sam Browning, Percy Creed, G. Davis, E. Gardiner, Bernie Gardiner, Frank Howell (who – the next edition of the paper said – ‘is not given to talking of his experience’) and Claude Mills were all present for the presentation of ‘a handsome travelling clock and umbrella’ to Miss Mabel Grist in gratitude for all her ‘splendid energy’ and hard work in organising the parcels sent to servicemen during the war. Private Smart (whom we have not identified) was still in hospital, and Alfred Harmer, from Toadsmoor, had died – ‘the gathering stood in silence when the chairman called his name’.

Percy Abel ‘spoke his deep appreciation…and believed that very few of them would have been alive now but for the food received from England’. There then followed a little concert.

The Bread Order was still in place, forbidding the sale of bread under 12 hours old, and coal was short.

The Hinton-Joneses were the instigators of another fund-raiser for St Dunstan’s – a production by the school of ‘Princess Chrysanthemum’, a popular operetta set in Japan, by C. King Proctor, performed at the Primrose Hall in late January. The ‘pretty oriental dresses’ and stage set with coloured lanterns and butterflies obviously made an attractive sight on a wet January evening, and the local performers were enthusiastically reviewed in the local paper:

…the Baby Butterflies was an improvisation and not actually a part of the operetta. It was a delightful addition to a composition brimming over with brightness and melody…

Bubbling along below the surface were urgent political discussions on the scarcity of housing, and public disquiet about the slow demobilisation of soldiers, sailors and airmen. The columnist ‘Jonathan’, writing on 10th January, refers to the resentment felt by many, going on to say:

At least the men who have broken the bounds of discipline have been handled with care, possibly because Bolshevism is too near to our shores to permit of bureaucratic sternness with Thomas Atkins…

He speculates that the disruption caused by the election, and the promises made during the campaign of ‘speedy demobilisation’ can’t have helped matters, but that ‘anybody with the capacity for thought must have known that a huge Army could not be disbanded by a stroke of the pen, and particularly having regard to the disturbed condition of Central Europe’ – where, after all, the trouble had all started.

A week later, the ‘Journal’ prints a digest of an article in ‘The Daily News’, which describes the ‘fears…in official circles’ that on the contrary, the demobilisation might be too rapid:

A high authority pointed out… that “the war is not yet over,” and that “Great Britain, in proportion to its military strength, must maintain an Army of Occupation on the Rhine for many months to come.

Apparently there is a new factor in the situation, which means that our object must no longer be rapid demobilisation, but the securing of the “fruits of victory”.

The intention seemed to be the creation of a dedicated ‘Army of Occupation’ – with strong discipline and decent pay, using ‘those categories of men who have done least during the war’ (this would not be likely to include those over 35). There was already a military presence in Russia, supporting the White Russians. The logistics of demobilising large numbers of troops was referred to:

Some misunderstanding may be caused by the statement which has been made that within a short time demobilisation may take place at a rate of 50,000 a day. While transport might be available to enable this to be done, it is understood that 40,000 a day is the highest number that can actually be dealt with.