Established in February 1915, St Dunstan’s Hostel for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors was soon overwhelmed by servicemen needing its programmes of rehabilitation. Its publicity and fund-raising activities seem to have been very effective, and there are many mentions of St Dunstan’s in the local press.

The ‘Journal’ of the 5th April gives a long account of a ‘Pretty Patriotic Pageant’ held at Chalford School in aid of the hostel. The concert seems to have been one of a series organised locally, involving the usual talents performing musical items, reciting poetry and dancing. The audience were addressed by Miss Marie Philpotts (possibly the 26 year old daughter of Harry Philpotts, a timber merchant, living in Thrupp in 1911?), who was obviously very persuasive:

“The vicar, the Rev. A E Addenbrooke, in thanking Miss Philpotts, confessed that to him her aptitude in pleading with an audience was a revelation, but with the quickened interest in women’s work and the increased political power she will now wield we may look for many surprises and a too tardy recognition of what women can undertake and accomplish.”

Casualties were mounting and the military effort required endless new blood (not to put too fine a point on it). In April 1918, the Military Service Bill (or ‘Man-Power Bill’) removed ‘reserved’ status from previously protected employments (e.g.on the railways or in agriculture), and extended the age limits on either end of the scale. Henceforth, boys and men between 17 and 50 would be expected to enlist. (The Bill also attempted to include Irish citizens in the conscription – but, to use a modern phrase, ‘Good luck with that’! No Irishman was ever conscripted.)

There was trenchant criticism of this latest plan from ‘Jonathan’, writing in the (politically Liberal) ‘Journal’:

“If as we are told, trained troops from America are to be the deciding factor in this war, to what end is it considered necessary to raise the age limit higher in England than in Germany or France, seeing that the benefits to be derived in a military sense are extremely meagre, and the disadvantages to trade must unquestionably be enormous?…I hope sincerely that Parliament will not permit a Bill to be hastily foisted upon the country just because Mr Lloyd George’s ‘business-like’ Administration has some ugly mistakes to cover up and finds the resort to camouflage the best way out of the difficulty.”

Any man between the ages of 18-51 who -despite all the hurdles – managed to gain exemption from military service was expected to serve in the VTC.

The call-up of even more men meant still more women were needed to fill civilian jobs, particularly on the land.

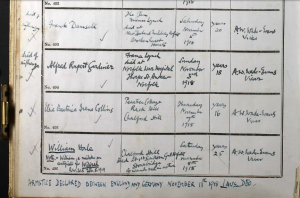

In their editions of 12th April, both local papers carried the news that the widow of Pte Gilbert Frank Damsell, had just received his Military Medal. Gilbert, ‘younger son of Mr Thomas Damsell of Chalford Hill’, succumbed to wounds received on 21st November 1917 a month later, on 21st December. He died in Boulogne, and was buried there with full military honours. A former pupil of Chalford Hill School, and a member of the congregation at Christ Church, he had joined up in April 1916 and left for France in July 1916:

“Always bright and cheerful, his memory will ever be cherished in Chalford and especially for the daring and fearless way he did his duty. Three times his name appeared for distinguished conduct…the Military Medal with bar awarded to him…for helping to establish a First Aid post, collecting wounded on the field, and dressing them under heavy shell fire.” (Stroud Journal)

He received his fatal head wound while bringing in casualties from the fighting. He was 25, and besides his widow, left a little son.

There was a happier tale about Pte Ernest Gardiner, who had been serving with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and whose parents lived in Marle Hill, Chalford:

“…having been wounded, [he] has been returned to Canada. Writing to his parents he says: ‘I am glad to tell you I am fine, and my arm is doing great. I will have a good arm again in time. I am now no longer a soldier, I guess, for I have my discharge. I have been to Waskada for two weeks, and had a good time. My landlady was pleased to see me, and there was quite a bunch at the station. Had I known that anything like that was going to happen I guess I would have stayed away. I was out to all kinds of parties, and the Returned Soldiers Association presented me with a watch for duty nobly done, as they put it…” (Stroud Journal)

The shortage of coal was leading to problems with the supply of town gas, and notices about a new Lighting, Heating and Power Order appeared in the press.

Mr William Halliday, of Chalford Hill, had received news that his son (name not given) had been wounded on the Western Front (presumably in the German advance). He had apparently initially been taken prisoner, ‘but managed to escape and crawl back to British lines’. He was now safely back in an English hospital. Mr Chas.Mills, of Ashmeads, had also heard that his son was wounded. A letter had arrived at the home of Mr and Mrs Daniel Barnfield, in Lower Hyde, written by their son Dick Barnfield, of the Glosters, after a worrying silence of eight months. The postal problems cut both ways – he hadn’t received any communication from home, either. He had apparently been away from the regiment on railway construction work. The ‘News’ remarked that Dick and his brother Bob, RFA, had been early enlisters from Chalford, ‘and both have been through the Gallipoli campaign, and later in Mesopotamia. Another brother, Tom, is at Gibraltar, engaged on garrison duties, and yet another, Albert, joined up on Saturday, with other members of the Gloucestershire Constabulary, of which he was a member’.

I have a copy of a photo of Dick Barnfield’s wedding to Lily Dickman in December 1914 – it comes from the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucester Graphic, and presumably shows two of his brothers as well:

Wedding of Dick Barnfield and Lily Dickman, December 1914

“Many Chalford soldiers have been and are engaged in the struggle on the Western Front, and, naturally, the greatest anxiety has been felt by relatives and friends…” wrote the ‘Journal’, on 26th April. Oakridge was badly affected, too. Among those mentioned in this paper and the ‘News’ was Albert Smith, son of Mr George Smith, of Oakridge, ‘who was an active worker in the Wesleyan cause before joining up’, posted as missing. His brother Archie had been wounded in the head. Tom Clark, son of Mr Clark of Primrose Mount, Chalford, had been wounded. L Acton, of Chalford, had been wounded, as had a son of Mrs Morse (Hyde Hill), serving with the RFA. In the death column of the ‘News’ was the announcement that Rupert James, ‘dearly loved elder son of Mrs Edith L Gardner (or Gardiner) and of the late Mr AJ Gardner of Pearley Cottage, Far Oakridge’, had been killed in action ‘in his 28th Year’. Walter Hunt, also of Oakridge, had been killed.